“The Daily Stoic” had an email it sent out yesterday, Father’s Day, that talked about Marcus Aurelius’ stepfather. Marcus was one of the great Stoics whose writings and philosopher still permeate our culture.

Part of the reason for that is Marcus’ stepfather.

“The Daily Stoic” writes,

“Marcus Aurelius’s father died when he was young. But then this young boy who was cursed by tragedy received a great gift. A gift that all children who have received it know to be one of the most incredible things in the world: a loving step-father.

“Ernest Renan wrote that, more than his teachers and tutors, “Marcus had a single master whom he revered above them all, and that was Antoninus.” All his adult life, Marcus strived to be a disciple of his adoptive stepfather. While he lived, Marcus saw him, Renan said, as “the most beautiful model of a perfect life.”

“What were the things that Marcus learned from Antoninus? He learned the importance of . . .

“. . . compassion, hard work, persistence, altruism, self-reliance, cheerfulness.

. . . keeping an open mind and listening to anyone who could contribute.

. . . taking responsibility and blame, and putting other people at ease.

. . . yielding the floor to experts and using their advice.

. . . knowing when to push something or someone and when to back off.

. . . being indifferent to superficial honors and treating people as they deserved to be treated.”

I think we often forget to “yield the floor to experts,” but that’s a post for another day.

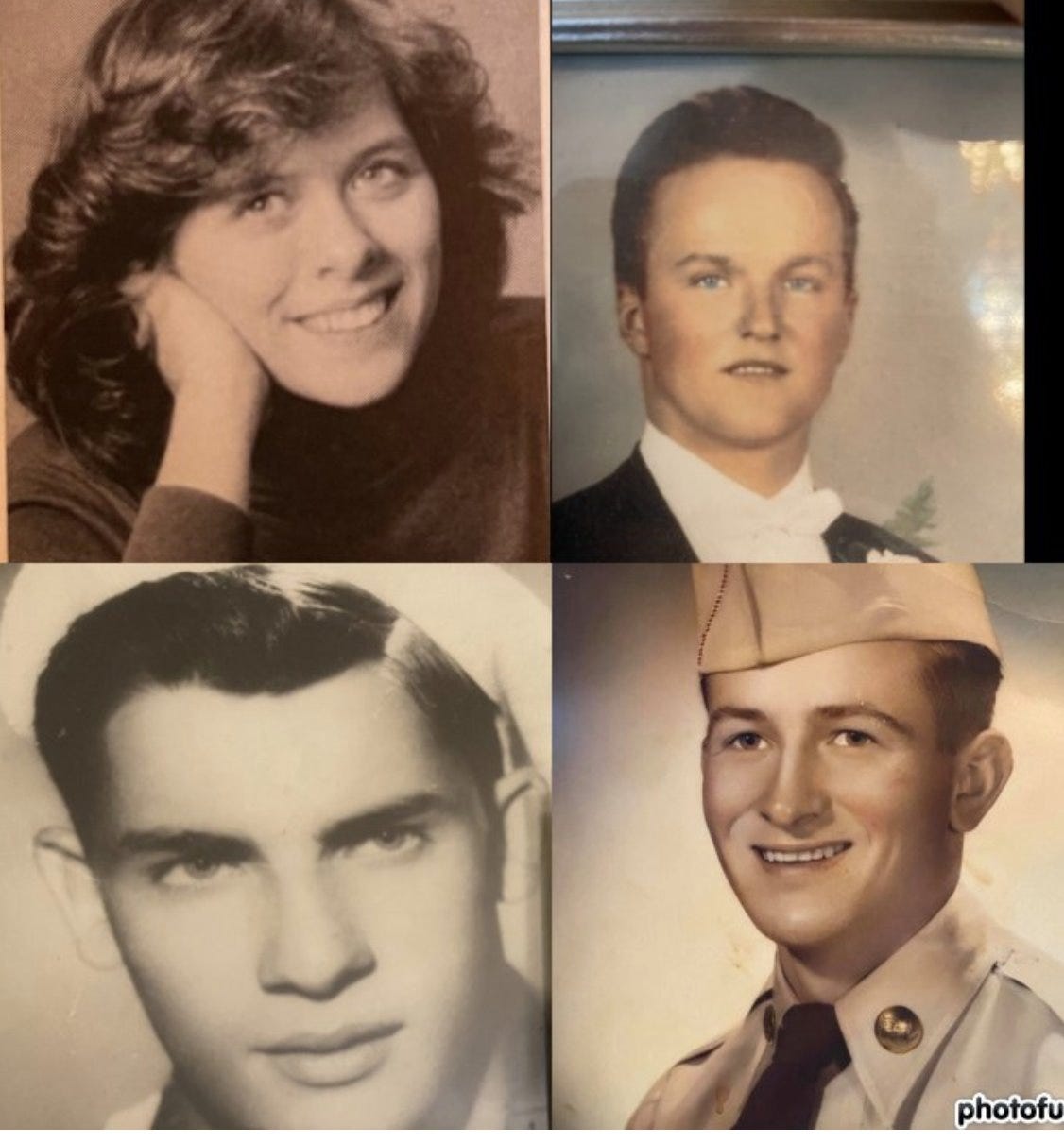

I write a lot about my little hobbit dad, but I don’t write a lot about my stepfather, John Palreiro. Sometimes I write about how his dark skin attracted racists when we were fishing in the middle of the New Hampshire woods and he taught me about respecting yourself and being calm in a crisis that makes no sense. Spoiler: Most crises don’t. Sometimes I write about how he gave me my first Grover when I was in the hospital in first grade, getting my tonsils out and taught me about using humor to make bad situations better.

My mom and dad loved each other when she was a teenager. She got pregnant. My nana allegedly ran him out of the state, threatening him with arrest and sent my mom to a relative’s house in Weare, New Hampshire. The baby was ill with cystic fibrosis. My mom said she was told he wouldn’t live and had no choice but to give him up.

Her heart never gave him up.

Her heart never gave up John either.

Decades later, he came back to New Hampshire. They were still in love. Every time they each heard certain songs (think Barbra Streisand, Englebert, Patsy Cline, ancient songs for ancient people), they’d think of each other. They married. I think she was his sixth wife or something wild like that.

The only time I remember them arguing was about a Portuguese meat pie and a lasagna. She thought that he liked his sisters’ recipes better than hers. This was apparently the ultimate insult.

I remember him standing in front of the picture window in the living room, trying to appease her, telling her that her lasagna wasn’t exactly the same though she’d used his sister’s recipe.

“No two cooks are alike,” he said, “even using the same recipe. That’s a good thing.”

He loved that—the difference in people. He was a contractor and a cabinet maker. His favorite stories were about people he met who created things: Grace Metalious, the woman who wrote Peyton Place, that he hung out with as a young man; John Updike who was kind to him in a bookstore; John Irving who was kind, too.

Difference was a good thing. Creativity was a good thing, too.

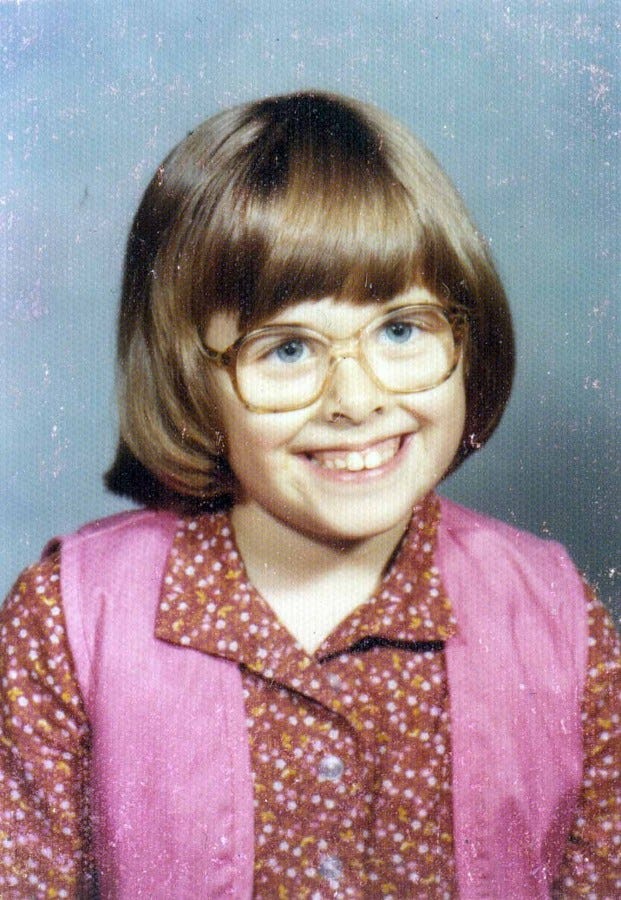

He allowed me to be my nerdy tomboy self with my big glasses. He bought me a race track, a train track, taught me to ride a bike, said I didn’t have to play with Barbies if I didn’t want to, taught me to fish, track in the woods, smell ferns, hug big and long.

When I was sad because I was goofy looking and sobbed and sobbed because some boy at recess told me so, he made me sit in front of the mirror with him, surrounded in a haze of Lucky Strike cigarette smoke. and stare at myself and say, “I am pretty damn beautiful. I, Carrie Barnard, am pretty damn beautiful.”

It was my first official swear word. I was in third grade.

He knew the power of words, of how a single word can change things inside your heart.

For the next two years, whenever I came into a room, he’d say, “Here she is, Miss America.”

He died when I was in sixth grade. He had a heart attack while we were having dinner at one of his sister’s house. He was 56.

And what did I learn from him?

I learned

. . . that you can try to have grace when you’re confronted with hate and that sometimes this is tremendously hard.

. . . to love while you have time to do and to not be afraid to show it.

. . . that everyone wants to be hero in their own story unless they give up and become the villain.

. . . treating yourself to ice cream is okay because you deserve to treat yourself.

. . . lasagna is delicious and seafood and spice are our friends.

. . . that you can find love again even when you lose it.

. . . that you get to define yourself as beautiful and remind yourself of it even when other people try to label you something else.

. . . that family doesn’t have to be blood. And sometimes? It’s better when it isn’t.

POSTS FROM LAST WEEK

I'm Not Annie Hall

When my first book came out, a local newspaper reporter interviewed me. She got some basic facts wrong, which ended up getting repeated in other newspapers, which is pretty funny. But what forever stays with me is that she called me ditzy—in a nice way.

Tips on Riding a Mechanical Bull

1. Act nice to the short man with the white mustache who runs the gears for the mechanical bull. This is important once you get on said bull. 2. Wonder why the bull looks SO much bigger in person. Touch its horns but not too much, this annoys the bull driver man with the mustache.

The podcast which I forgot to post here—it’s about Shaun running for office and the election on Tuesday.