Why I stayed out until 1 last night dancing

Fostering connections in honor of my dad and Grady

On one of the sidewalks in our town there’s the upraised outline of a dead mouse or maybe even a rat. Possibly a squirrel? It’s hard to tell.

It has been there for months. At first, I thought it was a drawing, and I inspected it a bit too closely because how cool would it be that someone drew a dark mouse outline on a gray sidewalk in the middle of winter.

It was not a drawing.

And then I thought that, eventually, it would fade, that the shadow outline of it would be gone, washed away by spring rains and summer foot traffic.

It is not gone.

And I don’t know what any of that means, but sometimes I think that life wants to make resonations even after it’s gone, make ongoing connections. Every time, I take the corner and start down that street and see that mouse/rat/squirrel/chipmunk, I try to imagine what its life was like, scampering about Bar Harbor’s downtown, living among the locals and the tourists and probably being pretty unnoticed until now.

When I used to go places with my dad, he’d always talk to the hostess or the cashier a little longer than most people would. He’d pause, sometimes touch their arm, make a comment asking them about something, usually their day. He’d stare right in their face.

“Why do you do that?” I asked him when I was sort of a snarky jerk in high school.

“Because everyone deserves to be seen. I want them to know that they’re seen, Carriekins,” he said.

Yes, he called me Carriekins. Not the point of the story, but probably why I was snarky in high school.

His words resonated though. He truly believed that tiny bits of connection could help the world. They certainly helped him. When my parents got divorced, my dad was depressed, really depressed. I remember him hugging me when I was little and saying, “I won’t know you. I won’t know my little girl.”

I didn’t get it. I was five.

But I get it now.

When my dad talked about how he made it through that time, he talked about his mom, his brother and his brother’s wife; he talked about his friends.

In Psychology Today, Grant Brenner writes,

Dispositional connectedness is “a tendency to value and prioritize interpersonal relationships.” People with high dispositional connectedness see other people as friendlier, are receptive to forming attachments, with greater emotional openness, expressions of affection and warmth, and communal feelings.

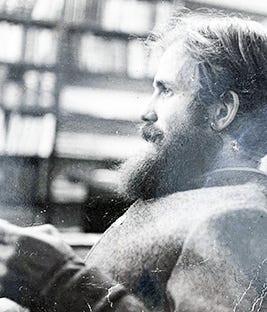

My dad was always agreeable. A social man who wanted to know everyone’s stories; he’d be fascinated by how people thought, how they achieved, how they loved, the more different their background and thoughts were than his? The better.

He believed in connection, but also in story and in people. When he was depressed right after their divorce and he went to a therapist, it wasn’t something men did at the time. There was a stigma about it, but my dad would just tell that fact about him out to the world; anyone could always know anything about him if they asked.

He wanted them to know him just like he wanted to know them. No secrets. Just truths.

Katie Styles writes on Psych Central,

Human connection is the sense of closeness and belongingness a person can experience when having supportive relationships with those around them.

Connection is when two or more people interact with each other and each person feels valued, seen, and heard. There’s no judgment, and you feel stronger and nourished after engaging with them.

Human connection can be a chat over coffee with a friend, a hug from a partner after a long day, or a hike in the woods with a family member.

Connecting with someone doesn’t have to always include words, either. Time spent in relative closeness and experience can also be a bonding experience.

Last night, Shaun (my husband) and I went to Lompoc, which is one of the cooler restaurants/bars in town. It’s been here for ages and it was my best friend, Grady’s favorite place though I hardly ever went with him. Lompoc was and is always a little too cool for me. That’s what I thought at least.

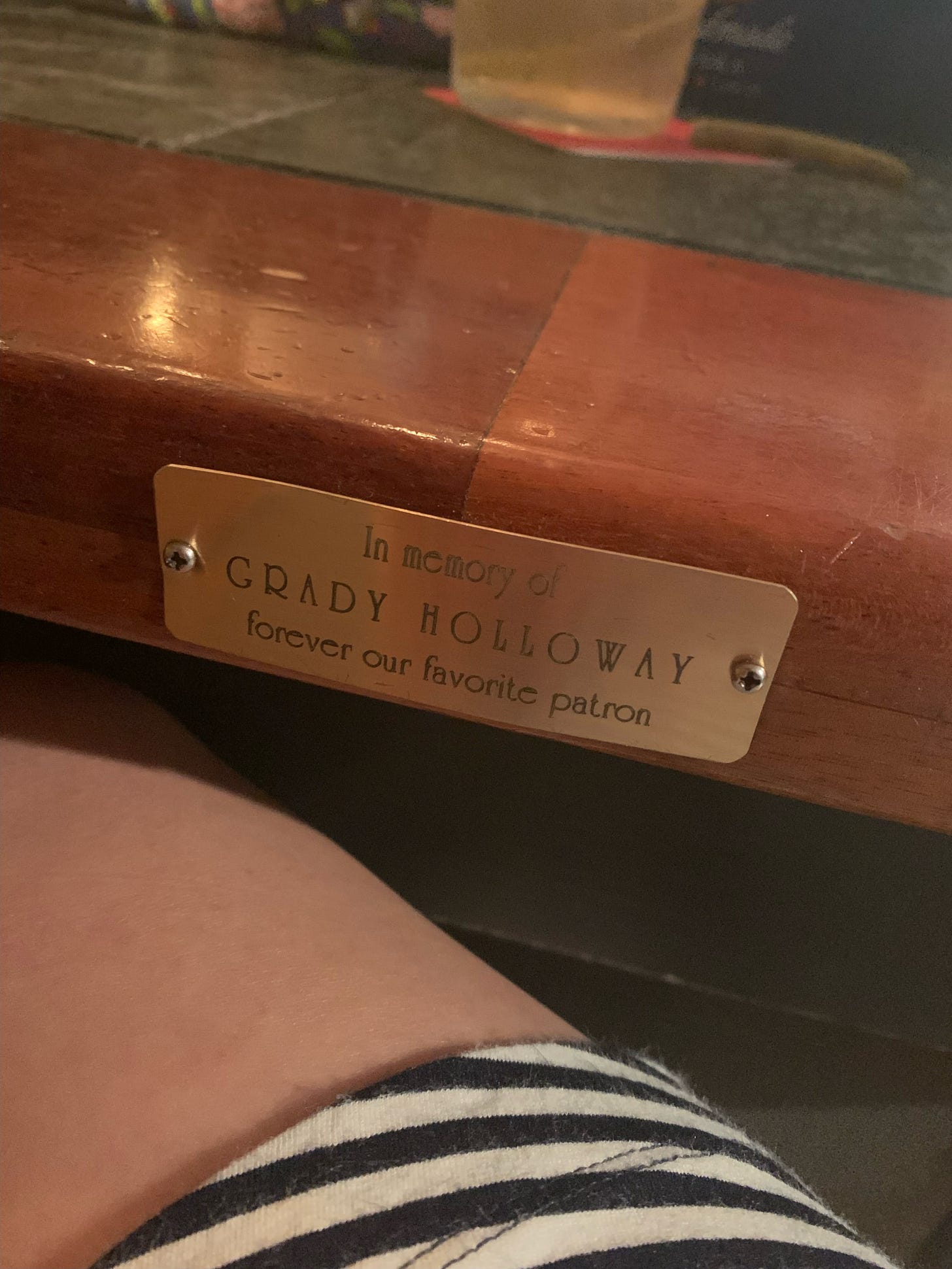

And some of our friends went there last night and one sent me this.

“Is Grady Holloway your friend you passed?” she asked.

My throat closed up a little bit. Shaun looked at me and said, “Do you want to go?”

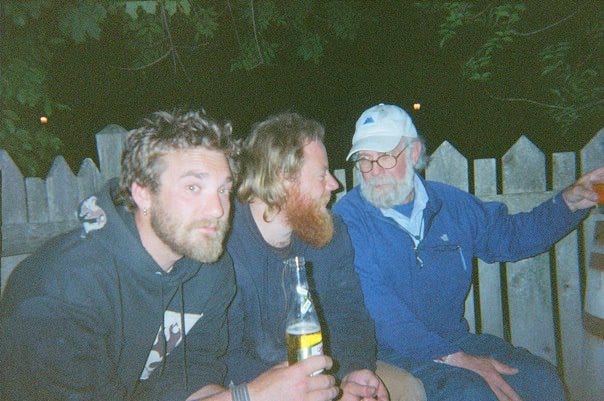

Grady went to Lompoc all the time because he was cool—so cool, but also, Grady, like my dad, believed in the power of other people’s stories and in connections. He was a taxi driver for a while before he became a newspaper reporter and editor. He was the type of guy who hung around with the Hunter Thompson set (as his obituary says), but he’d still hang around with me.

“Yeah,” I told Shaun. “Let’s go.”

I forgot to change clothes. I wore my ancient wool sweater in August and shorts. I’m not sure if I combed my hair. It didn’t matter. Going is what mattered.

Connections boost our mental health and has been linked to longer, happier, more fulfilled lives. So, we went to the Lompoc and joined our friends in Grady’s honor.

We danced in a crowded dance floor and were probably the second and third oldest people there. My friend went outside for a cigarette. I joined her after a bit. She got obnoxiously hit on, and Hatsana Phanthavong, a local restaurant owner, somehow noticed, came over to where we precariously stood on sidewalk and road, and saved us.

“She is a pretty girl,” he told the guys pointing at my friend and then pointing at me, “and she is a pretty girl, but they are not interested in you. They have other people.”

The guys got it. Sort of. And went away.

“I take care of my friends,” Hatsana said after and he reminded me so much of Grady right then. “I watch and notice. And then I take care of them.”

Grady loved Hatsana, too, because they were a lot alike. They watched. They noticed. They made connections. Those connections turned and turn into friendships. It’s almost like magic.

Someday, I’ll write more about Grady, but I’m not ready to yet. I think he’d get that. He’d say it was very Presbyterian of me.

BACK TO MY PARENTS

When my mom was dying, she sat up in that hospital bed and my older brother and sister used a plastic spoon to feed her some chocolate and vanilla ice cream from a tiny Styrofoam cup. The moment that first spoonful of ice cream hit her lips, our mother, with her eyes closed and her heart failing, broke into a smile that lit up her entire face with a joy so sheer and absolute that it brought tears to everyone’s eyes.

She was beautiful.

And she was dying.

And then she offered all of us some. She only had a tiny bit and she was enjoying it so much, but she still wanted to share, to give, to connect.

When my dad found out that he had a terminal, fast-moving cancer that a lot of firefighters from his time had, he told me on the phone. I was in Boston and I’d just been at the marathon where bombs had exploded. I was so shaken that night that I slept in my shoes—like at any moment I’d have to run away.

Dad gave me his details about the cancer. He had a month, maybe two, he said. But what he really wanted to know was how I was, what had happened, how we were, how people were doing.

I told him of walking back afterward, walking down the middle of the streets of Boston and Cambridge with people I didn’t know, about how strangers held each other’s hands, how they gathered around a girl who had broken down crying, lifting her up, rubbing circles on her back, listening to her sentences that were chopped apart with grief.

“You have to hold onto the good in people, Carriekins,” he told me, wheezing from the pressure around his lungs. “You hold onto that.”

He died less than two weeks later. It was about a year or two after my mom died.

It is hard to watch someone dying and in the time that my daughter Emily and I spent with my mom, I noticed something interesting in her murmurings. She called a lot for her brother Richard who she adored and who had died already. Sometimes she’d lift up her arm as if trying to grab someone’s hand, sometimes it was more like she was caressing an invisible face.

She often said with her eyes closed, “I see you, Richard. Richard. Richard, is it okay?”

I imagine he told her that it was okay. I imagine that she found that connection that she was searching for. And I hope and imagine we can all find that too, because what it is, is love. It’s acceptance. It’s memories and smudges on sidewalks and in our hearts. It’s hope and the generosity to accept others and their stories: perceived flaws and all. It’s the ability to find connection despite the devastation inside of you and around you. It’s pretty much magic.