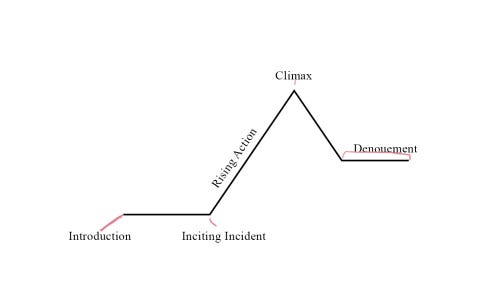

On yesterday’s podcast and the one a few before that, Shaun and I talked a bit about plot structures and narrative structures and how here in the U.S. we think of these usually (not always!) as pretty linear, and pretty much in a three-act framework (think beginning, middle, end) with rising stakes and drama as you go along.

This is not the only way to write.

It is just the dominant way to write in this part of the Earth right now for publishing.

I am very much a product of the U.S. culture. And I’m going to talk a tiny bit in the next couple weeks about different forms/shapes of storytelling, but again . . . I am a student of this culture’s structures. I am not an expert at other structures. I adore them though. I’m going to be providing links.

And hopefully by quickly talking about some of them, you might go off and explore and adore, too. Maybe even get an epiphany for your own story?

So, first as a refresher:

Western Storytelling:

Things you usually find here:

Character goals drive the story forward.

Characters are usually not static (they are in serials though) and they have emotional change and growth (or they devolve)

We want conflict and obstruction that keeps our characters from our goals.

If that conflict is resolved, goals met, character grows, it’s a positive arc. If not and they end up in a worse place? It’s a negative.

Where this structure comes from:

Aristotle and the Greeks, mostly

The belief that the individual and personal will matters

The belief that overcoming obstacles is positive

The siloing of society. We don’t think of fate as interconnected quite so much and it’s a bit more about polarities

Locke and his philosophy. Mills and his philosophy.

One Form of East Asian Storytelling: Kishōtenketsu

So, there are other ways of tellings stories and other influences in places that are not North America, right? And even IN places and cultures of North America. But I'm hopefully going to talk about that a bit more later.

One narrative model is “story without conflict” or Kishōtenketsu.

If you’re an American who hasn’t had a lot of contact with this, you’re probably thinking, “Wait. What?”

The Art of Narrative writes,

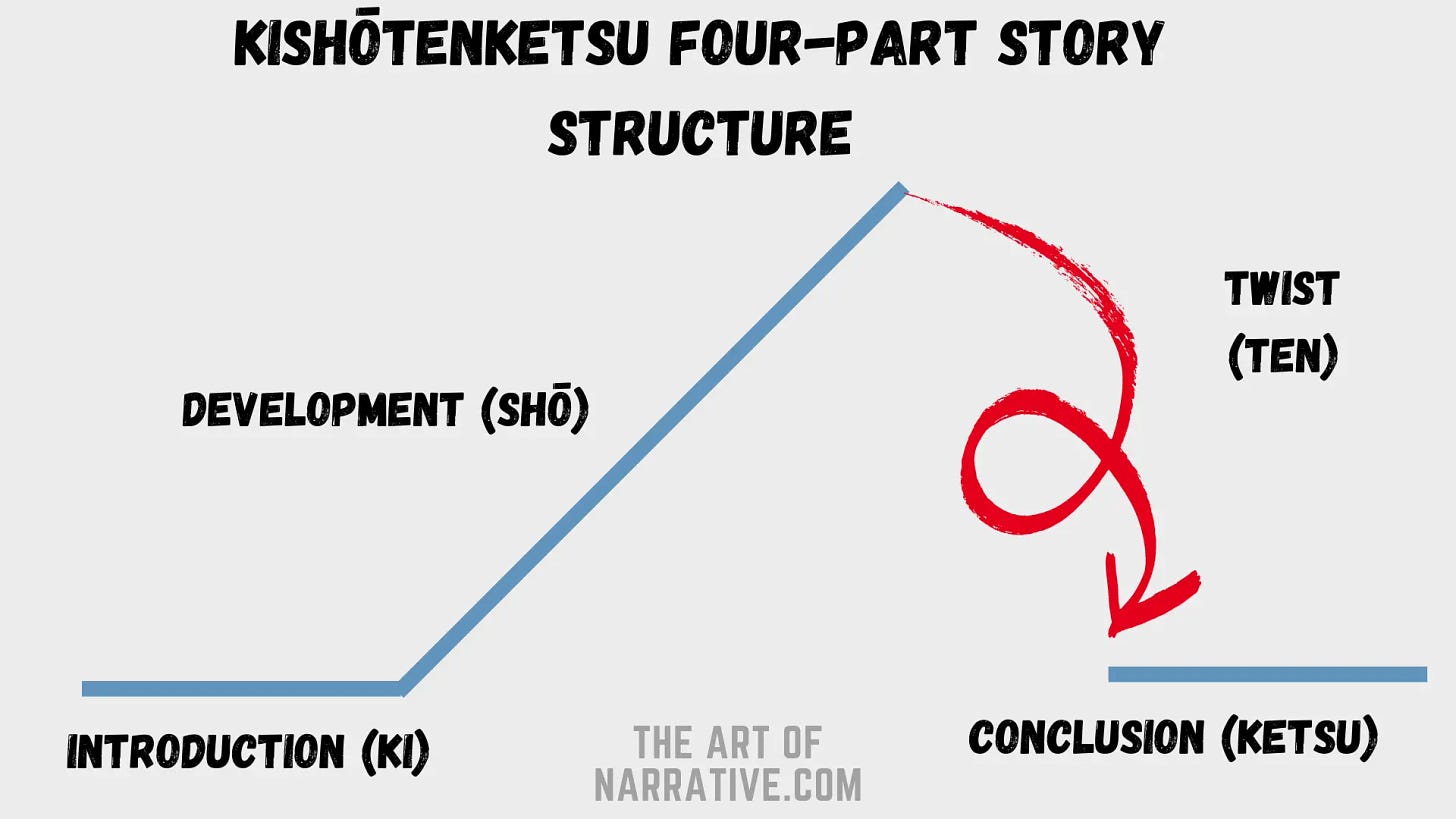

”Kishōtenketsu is a story told in four parts. This kind of storytelling is most closely associated with Japan, but it is also used in classic Chinese and Korean narratives. In fact, it was originally used in Chinese four-line poetry.“The plot of a Kishōtenketsu story relies on the third act twist. This is what puts the whole narrative into context. A traditional Western story starts by introducing conflict and builds to a climax. In Kishōtenketsu, the story is mostly set up that builds towards the story’s major twist.

The NovelSmithy breaks it down like this:

“Kishōtenketsu is a four act structure:

“Act One, or Ki, introduces the world and characters.

Act Two, or Shō, develops the characters and shows us their place in the world.

Act Three, or Ten, twists the story by showing a new perspective.

Act Four, or Ketsu, unites the new viewpoint with the beginning of the story.

“For example, we can see this structure in one of the best known poems of the Tang Dynasty, Spring Dawn by Meng Haoran.

“I slumbered this spring morning, and missed the dawn,

From everywhere I heard the cry of birds.

That night the sound of wind and rain had come,

Who knows how many petals then had fallen?”

It’s used in some manga and Studio Ghibli movies.

There’s a great post about it by 김윤미 Kim Yoonmi here. (She also talks about Aristotle’s two-act structure, which is super fascinating).

She writes,

”The origin of why East Asian 4-act came to be is roughly this: Economically, China set itself up early on to be interdependent on each other and cooperating–an Integrated economy. (Cecil 22:55-39:03) This meant, over time, there was famine, if there was yet another overthrow of the throne. China got TIRED of all the conflict, having to deal with famines, etc, and so pretty early on instituted the exam system (Han Dynasty), which helped mitigate the violence and allowed commoners to become officials (Cecil: 19:36-23:57). Conflict always, always was bad for the state. (27:30-29:00) qǐ chéng zhuǎn hé doesn’t have conflict at the center for that reason, and this is why development is the key. Also, why the third act of this version has usually some conflict, but it’s quickly squashed in favor of personal development. (Wesley Cecil: Podcast: 06-04 Chinese- Languages and Literature–Humane Arts 2015) I used this source since it reflects what own voices have said before to me privately.”

The NovelSmithy makes a couple of bullet point lists to explain this structure:

“Characteristics of East Asian Storytelling:

Story not primarily driven by conflict

Characters often reactive instead of proactive

Characters not goal driven (except maybe the villain)

Tension may not be introduced until late in story (if at all)

Ending emphasizing a perspective or aspect of philosophy

Ending might not be happy or tie up specific plot points

“Influenced by:

Buddhist ideals of goodness, karma, and conflict avoidance

Values of community, family, and prioritizing the greater good.”

But, honestly, it’s so great to go to people who know it, live it, do it, whose lives are creating this structure. So, if you have 12 minutes and you really want to understand it, these brilliant guys have it down and teach it on YouTube, which is pretty lovely and generous of them.

Do you have thoughts? Resources? Please, please, please feel free to comment with them. And I’ll try to find more too.