Someone I love wakes up every morning and thinks, “Ugh.”

This, obviously, is pretty common, but it’s also a pretty sad way to be. It’s hard to live happy when you’re dreading every day. All of my dads (I have three—long story) weren’t like this at all. Dad #1 was a truck driver and he’d hop out of bed, excited about hours and hours on the road. Dad #2 was a contractor and carpenter and he’d tell me, “Being alive still is enough reason to be excited. Dad #3 was a man who thought of each day as a chance for humor and maybe a conquest.

Not everyone feels this way. I would like everyone to feel this way.

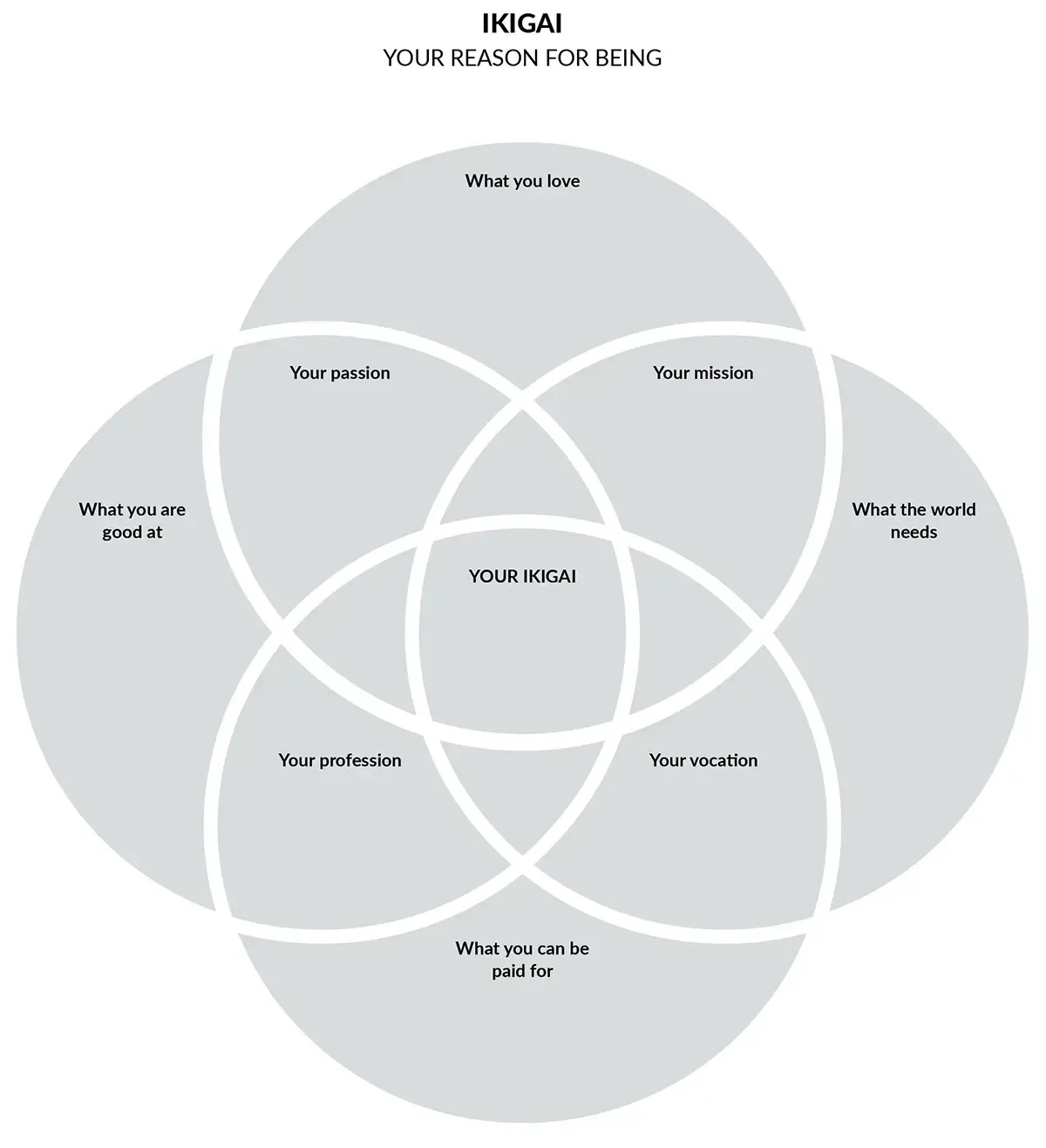

IKIGAI

I have a friend who is very good at solving problems and mechanical skills. He loves using his hands and he is great at staying calm under pressure. He is pretty addicted to adrenalin rushes. Having been deployed in the Army, he is skilled at a million things, but one of his favorite things is helping people in medical crisis—and fishing—but that doesn’t come into play here.

He’s an EMT, a firefighter, a nurse. And he’s a pretty happy guy. When I think about people who are pretty stable, pretty happy with life, feeling like they have a purpose and who lose themselves in tasks? I think of him. And now I also think about Ikigai.

WHAT IS IKIGAI

That turns out to be a really good question, but it’s at least partially related to waking up in the morning and feeling good about the day, about the life, about the purpose that is you.

There’s a post from 2020 by Jeffery Gaines, Ph.d, on Positive Psychology all about Ikigai, which I linked to on Saturday, but I didn’t really talk about it. That’s because I am no expert at all.

But that post is really really interesting to me and hopefully to you, too. Plus, it has graphics.

These diagrams are rather Westernized, so please know that. And many believe that they are a bit wrong because Ikigai doesn’t need to have anything to do with work. As the BBC writes, “For Japanese however, the idea is slightly different. One’s ikigai may have nothing to do with income. In fact, in a survey of 2,000 Japanese men and women conducted by Central Research Services in 2010, just 31% of recipients considered work as their ikigai. Someone’s value in life can be work – but is certainly not limited to that.”

That’s broken down in a lot of places in Western culture including MasterClass.

Anyway, Gaines writes,

“Ken Mogi, a neuroscientist and author of Awakening Your Ikigai (2018, p. 3), says that ikigai is an ancient and familiar concept for the Japanese, which can be translated simply as “a reason to get up in the morning” or, more poetically, “waking up to joy.”

“Ikigai also appears related to the concept of flow, as described in the work of Hungarian–American psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. For Csikszentmihalyi, flow occurs when you are in your “zone,” as they say of high-performing athletes.

“Flow is a string of “best moments” or moments when we are at our best. These best moments “usually occur when a person’s body or mind is stretched to its limit, in a voluntary effort to accomplish something difficult and worthwhile” (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990).

“Flow can be said to occur when you are consistently doing something you love and that you are good at, with the possible added benefit of bringing value to others’ lives. In such a case, flow might be seen as in tune with your ikigai, or activities that give your life meaning and purpose.

“It is important to note that ikigai does not typically refer only to one’s personal purpose and fulfillment in life, without regard to others or society at large.”

There’s also a MasterClass about this. You can see that link here. And a TedTalk about it here. And a tool to maybe help find it here.

I miss living in Japan. Thank you for this reminder of Ikigai.