I don’t often get political on here in obvious ways, but the measles outbreak in Texas has been hitting me a bit hard.

Honestly, it’s even wild to me that talking about vaccines is political.

But, as Carol Hanisch and Audre Lorde once said, the personal is political.

Vaccines are personal to me.

That’s because of my sort-of-uncle, Sam Katz.

But it’s also because of the Secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Robert Kennedy Jr.’s statements last week about autism and the people who have it. I am the bonus mom of a person who has autism. That human is actually the reason I started this newsletter. I was frustrated by all the stigma that our family faced—even in our lovely and adorable community.

But this post is mostly about Sam, who I’ve written about before.

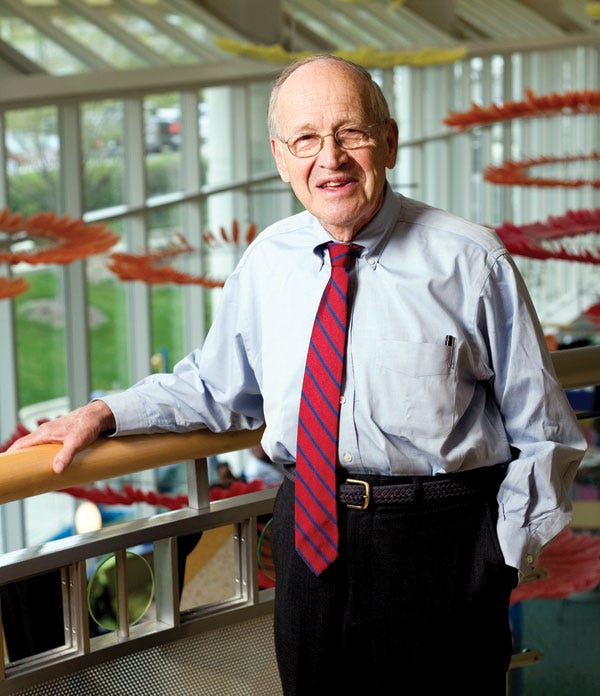

This is Sam. He’s pretty adorable, right? He used to get death threats. I’ve taken after him that way. But his threats were for a different reason. It’s because he was very much in favor of the measles vaccine.

How much in favor?

He was once considered the vaccine ambassador.

How much in favor?

Passionately in favor, so passionately in favor that he took a risk himself in the early stages of the vaccine’s development.

Back in 1955, polio struck Boston badly. It was an epidemic. Sam was a third-year pediatrics resident. I wasn’t born yet, so I wasn’t there, but I heard him talk about it on many Thanksgivings.

Dartmouth Magazine puts it simply, “Working on the hospital wards that summer was a transformative event for him, as he saw firsthand the damage the disease could do. The Salk polio vaccine had become available just a few months earlier, and children all across the country were lining up to get vaccinated. It was the beginning of the end for polio in the U.S., and the beginning of Katz's career-long interest in vaccines.”

Sam made policy. He researched vaccines. He administered them as a doctor. He educated people about them. He devoted his life to understanding vaccines and kids and medicine and people.

Science mattered to Sam. People mattered to him, too.

His wife, Catherine Wilfert? Same thing.

As Catherine’s Wikipedia entry says, “After 1993, using zidovudine during pregnancy led to an estimated reduction of mother-to-infant transmission of HIV in the United States by 75 percent[1] and a 47 percent decrease in new HIV infections globally.”

At one point some people passionately believed that the measles vaccine caused autism. At that same point people sent Sam death threats.

He talked about those threats and cast them (and his sister’s worries) aside.

“People are in pain,” he’d said. “They need a villain.”

We often need a villain apparently.

It was obviously no fun for Sam, but what he mostly worried about was people getting sick, about people being hurt, especially children. And Sam? He didn’t dig in right them into an us-vs-them mentality. It was a waste of time in a life where time didn’t need to be wasted. He made a decision to have empathy for the same people who were sending him death threats. They didn’t stop him. They also didn’t change him.

Sam was brilliant, obviously, but what made him really special was his empathy.

After Sam’s death, one of his former students Dr Robert Saul wrote, “One day I was asked to come to Dr. Katz’s office. ‘Oh no! What have I done?’ were my thoughts as I approached his office. He asked if anything was wrong. ‘People have noticed that you seem less jovial than usual,’ he said. I replied, ‘Well, my father is in Chicago and seriously ill with cancer. I cannot afford to go visit.’ He arranged for a plane ticket and time off. He said, ‘You can pay me back with a donation to the department after you are out in practice.’”

People mattered to Sam. It wasn’t about us-vs-them. It was all us.

“Walking with Sam through the halls at Duke was always a slow process. Sam knew the names of all the support staff working with pediatrics—the janitors, the unit secretaries, the lab techs, the nurses—and he would stop and talk with everyone. He knew their names, their spouse’s names, their children’s names, and sometimes even their pets. Sam valued people in ways that didn’t always reflect their station in the academic world—they were people and they mattered,” Ross McKinney , Kenneth Alexander, Stanford Shulman , Anne Gershon , Ravi Jhaveri wrote for the Journal of Pediatric Infectious Diseases after Sam’s death.

Sam testified before Congress and on “60 Minutes.” He worked and lived tirelessly. But of all the things I remember him being—jazz drummer like my grandpa, chocolate donut lover, ridiculously smart about the classics—he was not much of an us-vs-them thinker.

“We turn the world into us's and thems and we don't like the thems very much and are often really awful to them. And the us's, we exaggerate how wonderful and how generous and how affiliative and how just like siblings they are to us. We divide the world into us and them. And one of the greatest ways of seeing just biologically how real this fault line is is there's this hormone oxytocin,” Robert Sapolsky told the BIG THINK. “Oxytocin is officially the coolest, grooviest hormone on Earth because what everybody knows is it enhances mother infant bonding, and it enhances pair bonding in couples. And it makes you more trusting and empathic and emotionally expressive and better at reading expressions, more charitable. And it's obvious that if you just spritz the oxytocin up everyone's noses on this planet, it would be the Garden of Eden the next day. Oxytocin promotes prosocial behavior, until people look closely. And it turns out, oxytocin does all those wondrous things only for people who you think of as an us, as an in-group member. It improves in-group favoritism, in-group parochialism. What does it do to individuals who you consider a them? It makes you crappier to them. More preemptively, aggressive, less cooperative in an economic game. What oxytocin does is enhance this us and them divide. So that along with other findings, the classic lines of us versus them along the lines of race, of sex, of age, of socioeconomic class, your brain processes these us-them differences on a scale of milliseconds. A 20th of a second, your brain is already responding differently to an us versus them.”

Oxytocin is an interesting thing.

I know that vaccines aren’t popular for a lot of people in the United States right now. I know that it’s easy to vilify others. And sometimes even vilify science. Or maybe even oxytocin?

But science does actually have—you know—people behind it and some of those people? They devoted their lives to helping others—not for glory, for press junkets, for likes on social media posts, but to actually constructively try to make a positive difference.

I think all of us can all learn from that.

LINKS

QUICK NOTE

I send these emails twice a week. If you would also like to receive them, join the other super-cool, super-smart people who love it today.

*My WRITE BETTER NOW posts also come twice a week if you sign up for them, too, which you should. Cough. That’s me trying to sell. I am terrible at it, I know.

COMFORTING

I also have a once-a-week Substack over here and it’s mellow and I share a poem (not my own, God forbid, there’s nothing comforting about those), soup recipe, and other comforting things there.