Building Characters Using the Big Five

What is a Character Profile?: Tools to help you write your novel

Building compelling characters is something that most fiction writers want to be able to do. It’s a skill to make someone leap off the page (or the podcast or the screen) rather than just being flat.

And there are lots of ways to approach building character. One editor and script consultant, Kira-Anne Pelican, has an incredibly compelling piece on Psyche and has written a book about it. She deconstructs E.M. Forester’s more traditional approach and instead goes into character building via a psychological approach.

We’re all told to make characters complex. We aren’t often told how to do that.

Pelican reasons that we can do it via personality psychology and the Big Five model.

WHAT IS THE BIG FIVE MODEL?

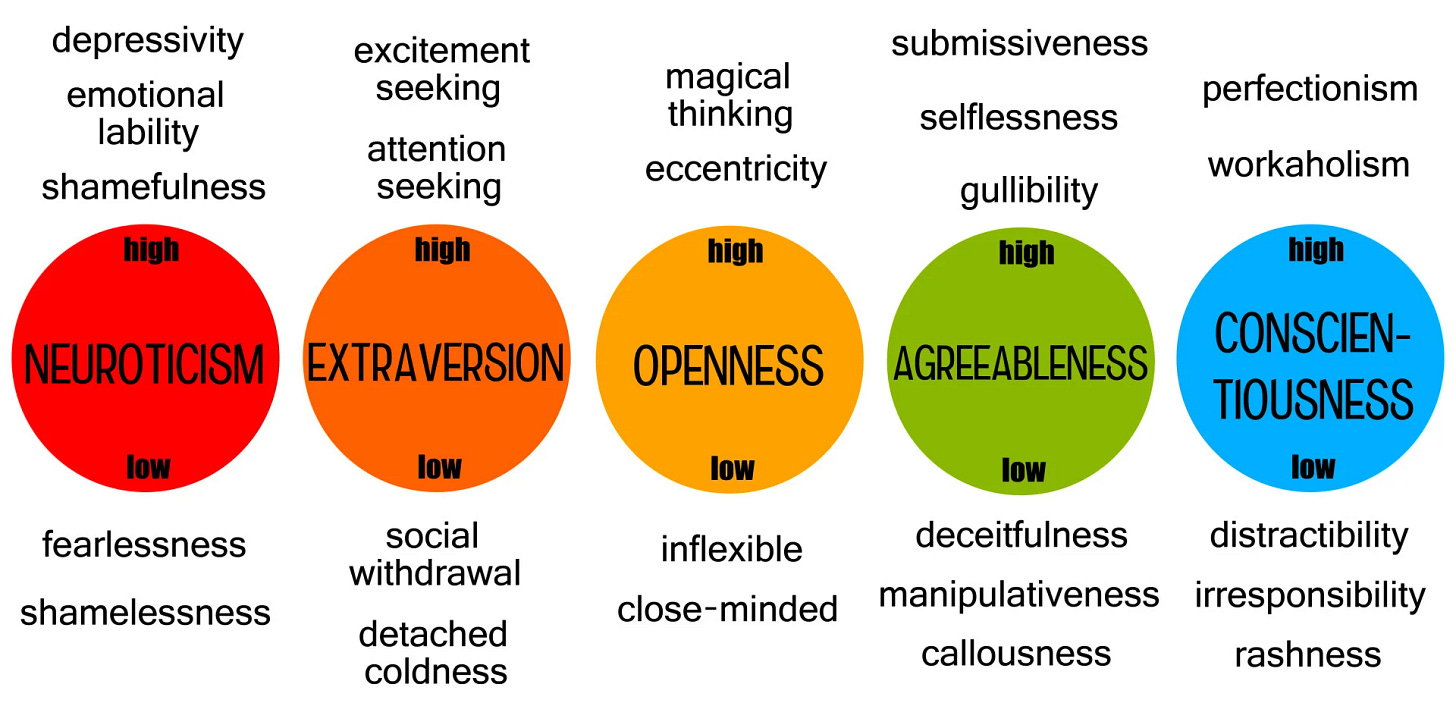

“The ‘Big Five’ model from personality psychology provides a comprehensive framework for reflecting on characterisation. The five main personality dimensions are at the very core of character, and shape how a character is likely to engage with the world, relate to others, experience the world emotionally, deal with responsibilities, and even speak,” she writes.

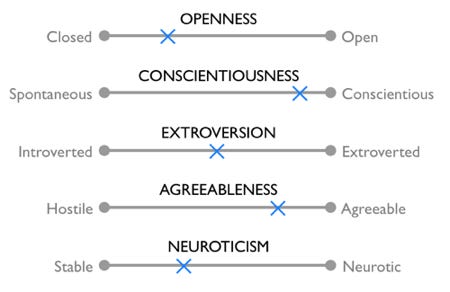

This is a lovely image via Simply Psychology that shows these traits and then the extremes. Here are a couple more, because I think it helps to understand it.

“The Big Five Personality Traits, also known as OCEAN or CANOE, are a psychological model that describes five broad dimensions of personality: Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism. These traits are believed to be relatively stable throughout an individual’s lifetime,” they write.

Psychologists Ernest Tupes and Raymond Christal created the Big Five approach. Paul Costa and Robert McCrae expanded it. These five attributes, they reasoned, are encoded in the language we use.

“They used factor analysis on personality survey data to reveal five broad semantic groupings among the words that we use to describe each other, and these have become the Big Five traits or personality dimensions: extraversion-introversion, agreeableness-disagreeableness, neuroticism-emotional stability, conscientiousness-unconscientiousness, and openness to experience-closed to experience. The idea is that these dimensions are independent of each other, so the degree to which a person rates on one dimension has no bearing on how they rate on any other dimension,” she writes.

So, how can we writers use this?

I’m summarizing Pelican through the Carrie lens below, but you should go check out her article and/or her book.

Look at the Big Five dimensions. Pick one that is the strongest in your character. Do not make this the strongest trait in all the other characters. Show this trait via language, action, and choice. Memorable characters are different. Lean into that.

Hang out with your character. Think about the real-life things that might have made them this way. What influenced how they talk, how they move (or don’t move) parts of their body, their word choice. What happened in their past made them who they are now.

Think about how your character will make your readers feel. Will they be into them? Hate them? Want to emulate them? Be worried for them? Why or why not?

Think about if your character is static or evolving. A static character doesn’t change during the story. An evolving character? Yep. You guessed it. She evolves. Pelican writes, “If you show your character expressing a variety of different traits at different times without any consistency, your reader will struggle to understand who this character is. Conversely, out-of-character behaviours that make sense given your character’s context and backstory are the most revealing and compelling to read. Use emotionally intense life events as catalysts of change for your character’s transformation.”

Good stuff, right?

MUSIC TO WRITE TO WHEN YOU ARE THINKING ABOUT THIS:

This adagio from “Spartacus” was sort of lofting around in my head this morning. And then, another very famous and popular writer shared it on their Substack, which makes me feel? Synchronicity, maybe?

Anyway, for one of you maybe this is meant to be something you hear today? Something that inspires you?

WHAT IS A CHARACTER PROFILE

This is a reshare from a bit ago with some changes and adding-in. Seeing that Psyche piece by Pelican made me think of this post. Some of you may have seen it before because I wrote and shared it before, but I’ve tweaked it a bit and it seems relevant to the discussion.

So, usually one of the first things an instructor will present in a character development class is the character profile sheet, but I tend to delay this whenever I teach because of my own belief system, which is probably something I shouldn’t admit, but it basically comes down to this:

I care more about my characters’ insides than their outsides. Yes, the demographics of who they are and how they grew up and their physicality absolutely impacts who they are, but I want their yearnings, wants, big lie, human worth and flaw to be the things that matter the most to me as the writer and the reader.

But character profiles are beautifully concrete tools and approaches that can truly help you nail down your character (not literally, no hammers involved).

A character profile is basically a tool that:

Helps you not get confused with the details as you write.

Helps you round out your character’s psychographics and demographics.

Organizes your thoughts.

Writerswrite.com says,

“A Character Profile is just meant to be a guide where you can list facts and details to help you get to know your characters, especially if you get stuck on one character who doesn’t quite seem real. You also want to be sure you don’t create a Mary Sue character. Maybe he needs a new characteristic — a hidden trauma, a fabulous skill or a deadly secret — something that will make the character come alive for you. If you are having trouble coming up with character details try to see how your character performs using a writing prompt or walk them through a situation known well to you.”

When I was in fourth or fifth grade, I loved character profiles, filling in all the blanks on the sheet, but what I didn’t know then is that while the profile is a fantastic organizational tool that helps you think about your character, it isn’t what makes your characters believable or lovable or be the kind of characters that readers want to invest time in.

Bringing life to the character doesn’t happen in the outline or the profile, it happens on the page as that character deals with conflict, goes after their yearnings, takes action, interacts and moves across the story, guided by their own yearnings that we readers can relate to.

Those yearnings are a much bigger deal than demographics because it’s those yearnings that make us (and our characters) human.

The character in your story is pretty much the key to make it all work, to inspire the readers to keep turning the page or scrolling down the screen.

Dwight Swain writes:

“A character is a person in a story.

“To create story people, you grab the first stick figures that come in handy; then you flesh them out until they spring to life.”

So, the question becomes how the heck do you flesh them out, right?

Matt Bird writes, “Character is the human element of your story, the aspect that the audience actually cares about.”

And that’s the big deal.

You can have the best plot in the world and most of the time, it won’t matter because people want characters that they can cheer for, commiserate with, worry about.

Bird believes that there are certain elements that need to be there for readers to care about your character:

They have to identify with them (the character).

The character needs to be resourceful.

The character needs to be active.

The character who is misunderstood is more lovable than the one who saves the cat.

The character doesn’t have to be likeable to be lovable. Go for lovable.

A character who is vulnerable is good and even a badass can be vulnerable.

In the Secrets of Story, Bird brilliantly splits three aspects of hero/protagonists into three needs:

Believe – They have to feel like the character is real.

Care – The reader has to be emotionally engaged with the character’s journey.

Invest – The reader has to be into the character. Bird says this comes from active characters who are resourceful and aren’t like the other characters in the book.

Bird further goes on to say:

But it’s his first bit that interests me the most right now.

Humans are stunningly complex. We contradict ourselves. We don’t always make sense and to encapsulate all of that in a novel is pretty impossible, so we have to pick and choose the contradictions and details to highlight. How do you deal with that?

Swain writes,

“A story is a record of how somebody deals with danger. One danger, for a simple story; a series of inter-related dangers, for one more complex.”

He advocates developing your character only so much as it is needed to deal with the story or to ‘fulfill his function in the story. You give an impression and approximation of life, rather than attempting to duplicate life itself.”

Swain believes that character begin with a fragment and then the author adds more and more on to that character, individualizing her until she becomes more real, more believable.

That individualization occurs through free association and layering in observations and details. What begins as a fragment of an idea (guinea pig hero) becomes a believable, lovable character as the author “supplements” that fragment with “Thought and insight.”

And that can be hard.

Swain thinks it’s hard because in real life, we tend not analyze people’s behavior and motivations. We take them and their actions for granted, he says.

“Consequently, when we try to build story people, we find that we lack a grasp of mental mechanisms: motivations.”

And motivations? They are a big deal. They are why characters go after goals. They are the yearnings that we readers connect to.

So, Swain says this is where the imagination steps in.

“To understand a man,” he writes,” you have to grasp the essence of that wholeness . . . its gestalt, the totality of its configuration.. . Each of us is an entity, a personal and private whole that transcends its components.”

I advocate taking a journal or diary when you're really lost developing a character and go somewhere safe and observe people, think about why they might be acting the way they are. What is it that's going on with them. Practice trying to understand people and you build those character development skills.

Resources/Links

https://www.writerswrite.com/characters/character-profile/

https://blog.reedsy.com/character-profile/

My favorite classical Substack