I’ve been talking a lot about plots and structure and the structure of narrative the last two weeks and I wanted to quickly talk about how there are some people who believe that some researchers from Vermont have figured out that there are only a certain number of story structures.

As Miriam Quick for the BBC wrote in 2018:

“In a 1995 lecture, Vonnegut chalked out various story arcs on a blackboard, plotting how the protagonist’s fortunes change over the course of the narrative on an axis stretching from ‘good’ to ‘ill’. The arcs include ‘man in hole’, in which the main character gets into trouble then gets out again (“people love that story, they never get sick of it!”) and ‘boy gets girl’, in which the protagonist finds something wonderful, loses it, then gets it back again at the end. ‘There is no reason why the simple shapes of stories can’t be fed into computers,’ he remarked. ‘They are beautiful shapes.’

"‘Thanks to new text-mining techniques, this has now been done. Professor Matthew Jockers at Washington State University, and later researchers at the University of Vermont’s Computational Story Lab, analysed data from thousands of novels to reveal six basic story types – you could call them archetypes – that form the building blocks for more complex stories. The Vermont researchers describe the six story shapes behind more than 1700 English novels as:

1. Rags to riches – a steady rise from bad to good fortune

2. Riches to rags – a fall from good to bad, a tragedy

3. Icarus – a rise then a fall in fortune

4. Oedipus – a fall, a rise then a fall again

5. Cinderella – rise, fall, rise

6. Man in a hole – fall, rise.”

Quick then created some really cool charts to show the look of the story structures. Like this:

These charts (she has six) are super fun, if a tiny bit reductive—like the whole concept.

But it also is fun because it creates shape to story, right?

There’s an absolutely brilliant book about story shapes.

The AutoCrit wrote,

”The Hedonometer: An emotional approach to narrative and story type

“More recently (and perhaps intriguingly) the University of Vermont took a leaf from one of author Kurt Vonnegut’s theories and used powerful computer programs to analyze data from 1,737 fiction stories. The purpose was to track the emotional content of the plot by looking for words such as ‘tears,’ ‘laughed,’ ‘enemy,’ ‘poison’ and so on.

Throughout any story, they describe building happy emotions as rise, and sadder emotions as fall. Their results concluded that there were six basic story types:

“Rags to riches” (rise).

“Tragedy,” or “Riches to rags” (fall).

“Man in a hole” (fall–rise).

“Icarus” (rise–fall).

“Cinderella” (rise–fall–rise).

“Oedipus” (fall–rise–fall).

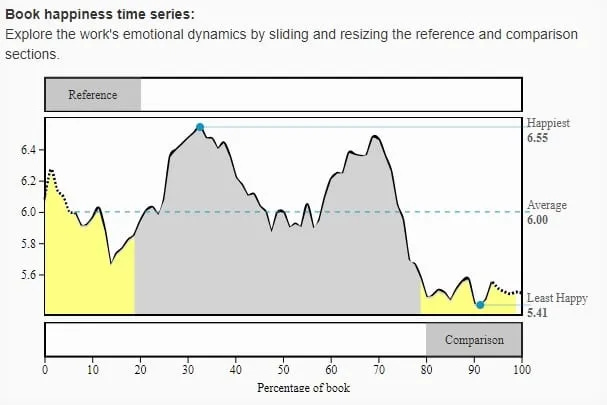

“Rather wonderful, however, are the emotion graphs produced to track the patterns of happiness during the narrative arc. Here, for example, we see the analyzed emotional arc of Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone by J.K. Rowling:

“Dubbed the Hedonometer, the results of this analysis for a wide variety of novels is also free to view online, and makes for a fascinating resource for writers who like to analyze books in detail.

“Of course, not every story in the world has been analyzed, but most of the classics and popular books are there for you to peruse. (It’s also worth bearing in mind that this most recent analysis only looked at fiction available on Guttenberg – mostly older classics and all in English. Deeper exploration of other cultures and recent ideas might uncover a wholly new story type.)”

And it’s just one way to look at story. And story shows us how cultures look at life. We shape the stories. The stories shape us. And variation? That’s a good thing.

Orson Scott Card wrote for Writers Digest that “all stories contain four elements that can determine structure: milieu, idea, character, and event. While each is present in every story, there is generally one that dominates the others.”

So, to him a story structure is either; milieu, idea, character or event.

That’s reductive, too. But headlines about FOUR WAYS TO WRITE A STORY or FIVE TYPES OF STORY STRUCTURE get hits, right? We all want to be simple, but stories? They aren’t that. They aren’t just data. They aren’t just formula.

Stories are mostly gorgeous and layered and complex, made up of chapters and scenes and paragraphs and lines and words that join together to make a voyage or an idea or a story. How cool is that?

Too cool to reduce really.